Nonviolent communication is an approach originally developed by the psychologist Marshall Rosenberg. It can be used as a tool to more efficiently resolve conflicts – and according to conservation scientist Brooke Williams, has great potential for science communication.

“It could prevent things from getting ugly in the keyboard wars”

In Germany, there is an ongoing public debate about wolves. They are listed as an endangered species, but their numbers have recently been increasing. Farmers and hunters argue for active management of the population. How could nonviolent communication be used in this kind of conflict?

Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is about trying to understand another person’s perspective, rather than just scientists coming in with the facts, which can unintentionally put people down a bit. If you don’t take the time to understand the other person’s position and don’t know what they believe, you won’t get very far in a conflict. NVC can help you reach an outcome more effectively.

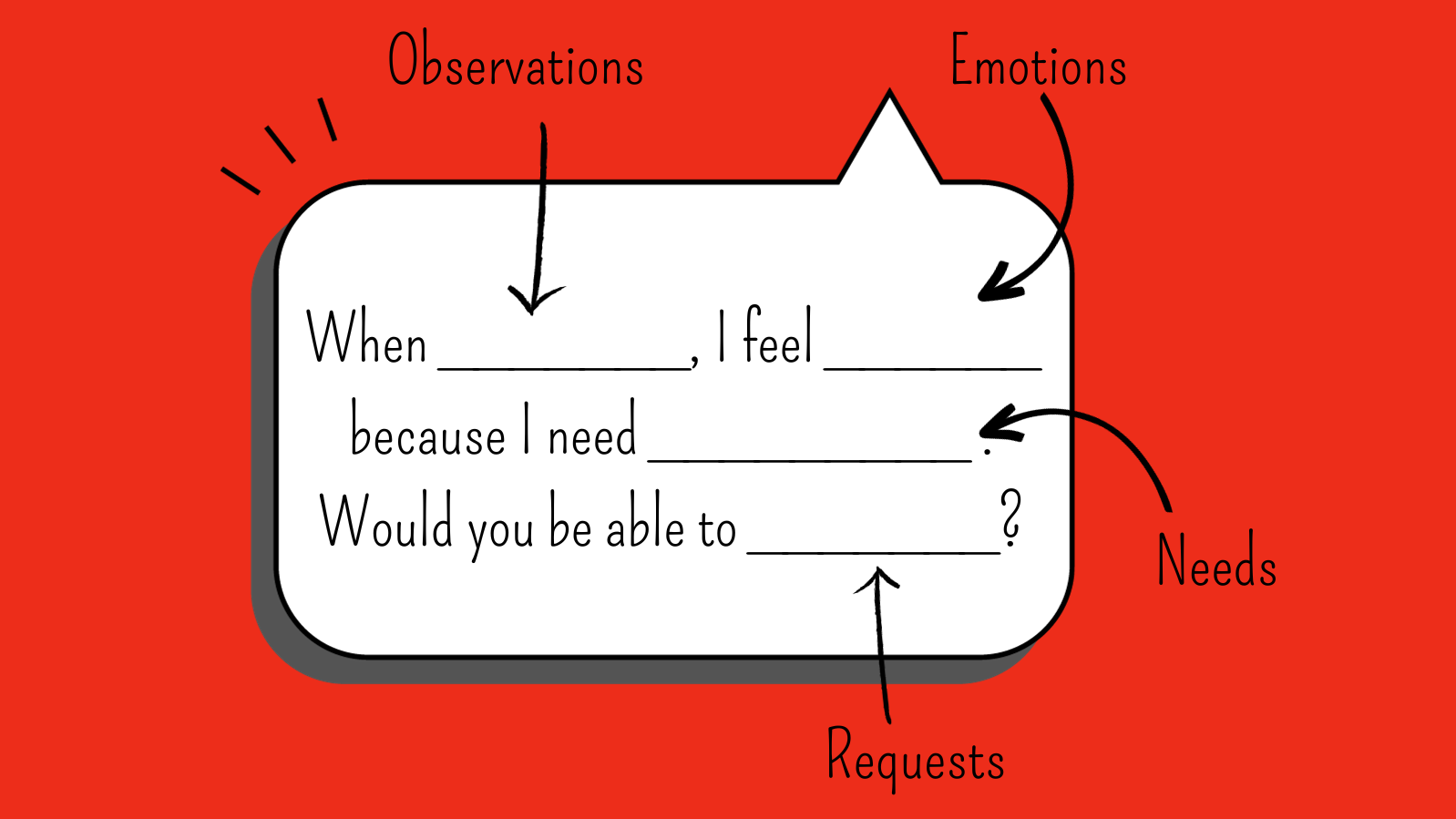

This communication technique consists of four steps: sharing your observations, feelings, needs and then making requests. In the wolves‘ situation, scientists or communicators would approach individuals as follows: “Okay, where’s the other side coming from? How are they feeling? Why do they have this need?” They try to understand and empathise and find common ground, rather than just saying: “Here are three scientific facts about why we can’t kill wolves”. The typical NVC process is aimed at one-to-one communication, but the concept can certainly be applied to media communication and communication to society and the public.

How can Nonviolent Communication help scientists explain the urgency of conservation issues without causing despair in their audiences?

Much of the messaging in conservation science is based on fear and a sense of urgency. In some cases, this can have the opposite effect. People can be very resistant to that message and feel misunderstood and not seen.

This communication strategy could shift the message away from this urgency. From our NVC perspective, you could highlight the benefits of moving towards a more sustainable world and frame it in terms of the wider benefits to individuals.

Often conservation is presented as being at odds with economic prosperity, as if you’re sacrificing jobs for conservation, but in fact we know that if we don’t go down a more ecological path we’re going to have much worse economic outcomes.

So, we need to essentially shift that debate towards the question: “Why do we need this?” Not just for conservation, but for human well-being, economic prosperity, jobs, and sustainable livelihoods.

Could this model help resolve social media debates?

Social media is a really tricky problem. For people arguing on social media, keeping these four steps in mind could probably prevent things from getting ugly in the keyboard wars or lead to a more constructive debate. But there are big problems with social media that are probably beyond the scope of nonviolent communication, like misinformation and bots.

In your paper, you compare the Nonviolent Communication model with dialogue and participatory approaches to science communication. Could you explain the connection?

A lot of the articles that we point out in the paper show a one-way approach to communication, along the lines of the information deficit model, which doesn’t work. This model typically assumes that the public has a gap in their scientific knowledge that can be filled by unidirectional provision of factual information. In contrast, dialogic and participatory science communication emphasises multidirectional communication, including listening to audiences, addressing specific audience needs, and recognising that audiences also have valuable knowledge or experience that can inform decision-making.

NVC is most closely aligned with dialogue and participatory approaches because it is a two-way communication style that seeks rather than assumes the “need” of the other party through empathic listening. What we’re suggesting is that when you’re solving conservation problems, it’s important to recognise that everyone has different perspectives and backgrounds. Communicating information in many different ways is probably the best strategy.

Do you have any idea when the model would not be the right approach to get your message across?

It will only work if both parties are open to finding common ground and if they are coming from an equal position of power. Obviously, there are a lot of power imbalances in conservation conflicts, for example when big companies are mining on communal land, where it is unlikely to be very effective in winning an argument or a legal battle. It might also be the case that the other person has ulterior motives and is not interested in finding common ground at all, in which case Nonviolent Communication probably won’t be very useful either. It’s really effective when both parties are interested in resolving the conflict.

How can scientists and science communicators deal with criticism from the public while maintaining a constructive dialogue?

It’s hard not to slip into a more aggressive style of communication, but they could try as best they can to stick to the nonviolent communication approach. We have highlighted the differences between these two contrasting styles in the paper, using specific scenarios that people might encounter. Using the initial example, one scenario could be farmers or hunters seeking to kill wolves to protect livestock, while another member of the community may be concerned about protecting that same wildlife.

The community member could communicate their observation (“When I see traps being set that will kill wildlife…”), their feelings (“…I feel really worried because it is so important to me that this ecosystem, including all of its plants and animals, remains intact.”), and their needs (“I grew up here, and I need to know that the next generation will be able to have the same wonderful experiences I did with nature.”)

Based on this, they could make a request: “Would you consider trying improved fencing as a solution instead of killing the wildlife?” But it’s difficult with online criticism. People can have very ‚out there‘ views on certain issues and come from very different backgrounds. It’s a constant challenge for everyone, conservation scientists, politicians, communicators and so on. If someone disagrees with your message and does not believe what you are saying, even though you have tried to communicate in the most effective way possible, then you just have to accept that.

What advice do you have for scientists interested in using nonviolent communication in their work?

I would suggest trying different approaches and styles and see if you get an improvement in the way your communication is received. Maybe you’ll see a change in response. There is no one-size-fits-all communication technique. As you go through your career and come into contact with different kinds of conflicts and discussions, you will find out what works where. Nonviolent communication is one tool, but there are others that might be useful in different contexts or with different people. So, explore and experiment!

Further reading

Williams, Brooke A., et al. „The potential for applying “Nonviolent Communication” in conservation science.“ Conservation Science and Practice 3.11 (2021): e540. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.540