How can street art reinforce a sense for environmental issues in local communities? Australian street artist BOHIE and communication scholars Blake Thompson and Dr Anna-Sophie Jürgens reflect on their recent collaborative paper.

“I didn’t even know my work was considered science communication”

BOHIE, as a street artist, you collaborated with Blake, Anna-Sophie and Dr Rod Lamberts on a scholarly article published in the Journal of Science Communication about the potential of street art as a form of science communication for environmental issues. How did this collaboration come about?

BOHIE: I was approached by Anna-Sophie and Blake, who told me that they were interested in street art as a form of science communication. I didn’t even know my work was considered science communication. I was just trying to create a bit more space around a topic that can help someone to potentially see it slightly differently. So, if that’s science communication, then great!

Blake Thompson: We connected with BOHIE when we went to Canberra’s first ever street art festival last year. We were able to meet with many street artists and hear more about the background of their art and what the inspiration was behind their ideas. We then came up with the idea of writing about street artists and how they are communicating environmental ideas in a way that engages people.

Anna-Sophie Jürgens: At the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science (CPAS), among many other exciting research streams, we study science in pop culture. We explore pop culture as a complex multimedia realm where collective science understandings are created, shaped and envisioned. Pop culture includes comics, animation, film, pop music and many other phenomena that are prevalent in a society at a given point in time. The field is massive. Street art is a part of pop culture. The beautiful thing is when you walk past a street art mural in a city, you are exposed to it, whether you want it or not. It can be a very powerful tool to address different and diverse audiences.

One of the murals featured in the article is “In Our Hands”, which depicts the 2020 bushfires. Could you explain the thought process behind this artwork and elaborate on its visual elements?

BOHIE: This was a collaboration with the artist Faith Kerehona. The brief was to respond to things that were important to the community. We wanted to guide the conversation towards the bushfires that Canberra suffered from in the beginning of 2020. We gave out a survey to the local community and asked them what changes they had noticed in nature since the bushfires. It was clear that there was a general concern for wildlife.

Our thought process for the “In Our Hands“ mural originally started with a woman floating in water surrounded by rubbish. To the rest of the world climate change may look like the sea level is rising, not necessarily bushfires. However, living in the bush and being surrounded by bushfires myself, I didn’t want to paint bushfires on this big wall. It shouldn’t be too close to the audience: the fire itself would sort of be reaching into real life. So, we found a middle ground. It became really important to us that the cool blue water contained the fire.

Another important element are these floating flowers, which are native orchids. They were actually the first to regenerate after the bushfire. As the concept developed, we were just adding more information to it, like the woman is cradling a baby kangaroo. The Joey’s got bandages on its feet, which stems from my own experiences. I saved a Joey during that time and saw a photo of it in a kangaroo hospital afterwards.

BOHIE, in a video about your work you said: “How people receive my art is totally out of my control”. How do you make sure that the scientific message is still understood?

BOHIE: I can’t. The best that I can do from my perspective is to try to simplify the visual message as much as possible. Anywhere that they land, even within a grey area, should still get the audience to somewhere where I want them to be.

How can artists and scientists work together to get a message across?

BOHIE: Individual artists and scientists work differently. But I think the collaboration of arts and science can be a perfect fit. I benefited so much from these collaborations.

We artists speak a more accessible language. Scientists collect data and put it out to the public in a report, written in heavy, intellectual language. However, visual art is especially accessible in the public space regardless of language barriers. Collaborations between artists and scientists can be harmonious partnerships in the sense of two opposite ends of the spectrum, but still telling the same story.

Jürgens: Yes, and these collaborations can also be transformative. Working together with BOHIE specifically, we science communication researchers have developed a new and sharper understanding of the importance of process and different logics: the process of working together and understanding how we actually understand terms like ‚research‘, ‘writing’ and ‚environment‘ that we had somewhat taken for granted. We were – and still are! – fascinated by how BOHIE’s art is able to make visible what is difficult to put into words; this includes the fragility of the environment and the urgency to act in the face of our climate emergency, but also broader values and collective experiences.

In the paper, you wrote that “enjoyment of science-related content does not require the audiences to fully engage with the science”. Could you explain what role enjoyment plays in science communication?

Jürgens: Research shows that enjoyment has a positive effect on learning and memory and can increase interest in and engagement with science.

Thompson: There is a lot of messaging around environment and climate change that is doomsday-esque. But we can also use positive reinforcement to communicate about the environment. It can make people feel less hopeless. Bringing a human element into the topics that are relevant to the people around the artwork, can generate engagement in these scientific topics.

When creating artworks on environmental issues, what practices are important to keep in mind?

Thompson: I think one of the most important things is understanding the values of your audience. If you don’t appeal to your target audience, then there is no personal connection or engagement. BOHIE would speak to the locals when she was creating her street art. She found out about their stories and created something that appeals to them.

BOHIE: It’s an interesting dilemma. The people who are commissioning a piece or who I am partnering with on the research of the piece, for example environmental scientists, they all have opinions on how the artwork should turn out. But I also have to keep the community in mind, who will be existing and living alongside the artwork out in the public space. They are our audience. I have to make sure that they are not too challenged by the artwork and develop a blind eye and look away. It has to be hopeful enough, but also intellectually engaging enough for them to want to not only look at it once, but to sit with it and try to understand it.

Street Art in public spaces can trigger all sorts of responses – what has the reception been like?

BOHIE: In general, it’s hard for us to monitor the response. People come up while you’re painting and say positive things, but the people who don’t like it generally will pass. In my experience with “In Our Hands”, the most feedback I heard was that people felt like it spoke for them. It symbolically seems to summarise people’s care for the natural environment here, which had been so badly burned during the bushfires. We all felt overwhelmed by the gravity of the situation and by the amount of species that were lost – it was so devastating. To create an artwork that helps people feel like there is a sense of hope, and that we are all connected – it resulted in some really positive feedback.

Do you think street art is useful as a science communication tactic beyond environmental science?

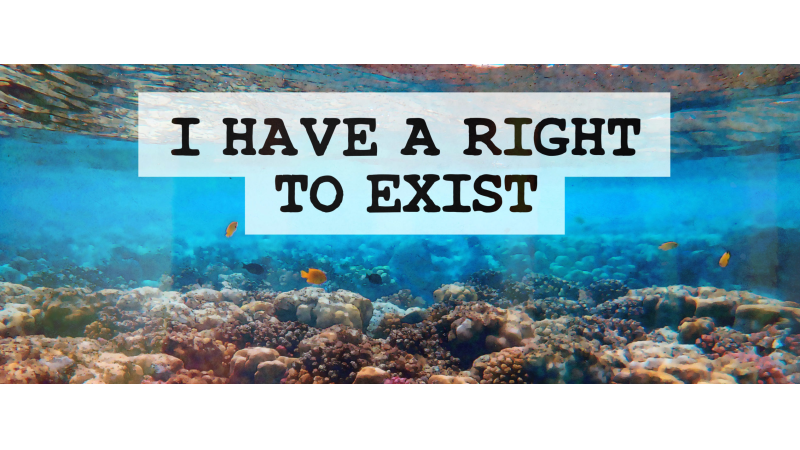

Thompson: A hundred percent. I think there is room for street art talking about all kinds of different topics. I was in Taiwan a couple of months ago and there was this beautiful mural of aquatic life all along the beach on a little sea wall. We mentioned in our paper that when a positive relationship and interest in science is generated through media such as art, it can lead to people pursuing it in the future at a more professional or academic level.

BOHIE: I was travelling in Mexico earlier this year and was inspired by the social justice elements within their history of street art. Mexico has a rich history of Revolution in street art.

Jürgens: Street art often questions who owns public space and it can have a political dimension to it. The revolutionary aspect is also very present in the research. For example, there is very impressive research on the idea that street art can express political sentiments and thus be a form of protest. There are many different and fascinating perspectives on and around the communicative power of street art that can really spark a conversation.